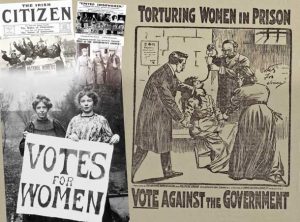

When the British prime minster Asquith visited Dublin on 18 July 1912, Hanna Sheehy Skeffington and other members of the Irish Women’s Franchise League paraded with posters. Asquith, who was dependent on the vote of the Irish Parliamentary Party to keep him in power, was an opponent of the franchise for women, as indeed were both John Redmond and Carson; it was about the only thing they all agreed on.

When the British prime minster Asquith visited Dublin on 18 July 1912, Hanna Sheehy Skeffington and other members of the Irish Women’s Franchise League paraded with posters. Asquith, who was dependent on the vote of the Irish Parliamentary Party to keep him in power, was an opponent of the franchise for women, as indeed were both John Redmond and Carson; it was about the only thing they all agreed on.

Sylvia Pankhurst described how local suffragists met Asquith when he arrived by boat at Kingstown and shouted at him through megaphones. ‘They rained Votes for Women confetti upon him from an upper window as he and Redmond were conducted in torchlight procession through the streets, but when they attempted poster parades and an open-air meeting close to the hall where he was speaking, a mob attacked them with extraordinary violence.’

The mob was allegedly led by the Ancient Order of Hibernians ‘determined to punish womanhood for the acts of militant women from England’. Innocent bystanders were attacked and forced to take refuge in shops and houses; several, including Constance, were hurt. During the parade on 19 July, an English suffragette Mary Leigh had thrown a hatchet into the carriage holding Asquith and Redmond as it passed over O’Connell Bridge. Around the hatchet was wrapped a text reading ‘This symbol of the extinction of the Liberal Party for evermore’ .The hatchet missed Asquith but struck John Redmond, who was travelling in the same carriage, on the arm.

Later, she and Gladys Evans ‘made a spectacular show’ when they set fire to the Royal Theatre where Asquith was due to speak the following day. As the audience was dispersing, Leigh flung a flaming chair over the edge of the box into the orchestra. Evans for her part set fire to a carpet ‘then rushed to the cinema box, threw in a little handbag filled with gunpowder, struck matches, and dropped them in after it.’ ‘Several small explosions occurred, produced by amateur bombs made of tin canisters, which with bottles of petrol and benzine were afterwards found lying about.’

Their stunt attracted much publicity and widespread criticism. On 7 August 7 1912, Evans and Leigh along with Jennie Baines (‘Lizzie Baker’) and Mabel Capper , all members of the Women’s Social and Political Union,were tried at the Green Street Special Criminal Court in Dublin for ‘serious outrages at the time of the visit of the British Prime Minister Herbert Asquith’.

The trial lasted several days with the police initially refusing permission to other women to attend. After Leigh and Evans were sentenced to five years prison in Mountjoy, and denied political prisoner status. The sentence to penal servitude – a first form the suffragist movement – was greeted with outrage in Britain. From the Women’s Social and Political Union came a statement calling the sentences an ‘an outrage which is not devised as a punishment to fit the offences, but to terrorize other women.’ A petition was raised against the sentencing, saying the ‘purity and honesty of the motives of the accused were questioned by no one’ during the case, and arguing that the sentences were ‘far in excess of those that were ever passed down in the United Kingdom’.

Leigh and Evans were warned that under no consideration would they be set free, although Baines and Capper, who had been sentenced to seven months each, were quickly let go. They went went on hunger strike. Leigh was force-fed for forty-six days until her release on 21 September 1912. Evans went on hunger strike on her arrival at Mountjoy Jail and was force-fed for fifty eight days until her release on 23 October 1912 due to ill-health.

The behaviour of the militant suffragettes was seen as an attack on Home Rule and caused much ill feeling in Ireland, with the Irish Women’s Franchise League, led by Hanna Sheehy Skeffington, distancing itself from the behavior of the English visitors.

On 14 December 1918, the first general election to be held after the Representation of the People Act 1918 was passed and so the first election in which women over the age of 30, and all men over the age of 21, could vote. Previously, all women and many poor men had been excluded from voting. The bill had been passed into law on 21 November after the ending of World War 1.

Of the seventeen women who stood as candidates in December 1918, only nine were adopted by the Liberal, Labour and Conservative parties, with a further two representing Sinn Fein. The remaining six stood as independent candidates backed either by existing organisations such as the Women’s Freedom League or by the new Women’s Party which had emerged from the remains of the Women’s Social and Political Union.

Although then detained in Holloway Prison, London, Constance Markievicz stood for Sinn Fein in St Patrick’s Ward, Dublin, and was the only one elected. Other Irish women who stood for election were Winifrid Carney in Belfast and Charlotte Despard in London. On Sunday December 29, the day after the results were announced, Markievicz was told that she had been elected: ‘Madame got so excited she went yelling and dancing all over the place,’ said her sister detainee, Kathleen Clarke. In the St Patrick’s Division, Constance polled 7,835 votes; William Field of the Irish Parliamentary Party, who had held the seat for twenty-six years, got 3,741 and Alderman JJ Kelly 312 votes.

Outside the Sinn Féin headquarters on Dublin’s Harcourt Street, an excited crowd had watched as the figures from the counting centres were displayed on a giant notice board in a second floor window. That Sinn Féin could win by such a huge margin was the stuff of dreams. ‘The humbug was now over’ as Joseph Cleary said when speaking on behalf of a triumphant Markievicz. Not everyone was pleased with her election. A leader in the Irish Independent questioned her ‘mental balance’; this ‘mean and unjustified attack’ provoked angry letters to the paper from Maud Gonne McBride and Jenny Wyse Power. Markievicz would become a member of the first Irish Dail in 1919 and only the second woman in Europe to take up a ministerial seat after Alexandra Kollontai in Russia.

Outside the Sinn Féin headquarters on Dublin’s Harcourt Street, an excited crowd had watched as the figures from the counting centres were displayed on a giant notice board in a second floor window. That Sinn Féin could win by such a huge margin was the stuff of dreams. ‘The humbug was now over’ as Joseph Cleary said when speaking on behalf of a triumphant Markievicz. Not everyone was pleased with her election. A leader in the Irish Independent questioned her ‘mental balance’; this ‘mean and unjustified attack’ provoked angry letters to the paper from Maud Gonne McBride and Jenny Wyse Power. Markievicz would become a member of the first Irish Dail in 1919 and only the second woman in Europe to take up a ministerial seat after Alexandra Kollontai in Russia.

******

In the years following, political parties remained reluctant to select women as candidates. Nancy Astor at Plymouth in 1919, the first women to sit in the House of Commons, as well as Margaret Wintringham at Louth in 1921 and Mabel Philipson at Berwick upon Tweed in 1923, were all elected at by-elections and all took over seats previously occupied by their husbands.

Note: The term suffragette was invented by newspapers of the time to describe the more visible activists, particularly members of the British Women’s Social and Political Union, led by Emmeline Pankhurst, who were influenced by Russian methods of protest such as hunger strikes. The word suffragist is a more general term for members of the suffrage movement, particularly those advocating women’s suffrage.

Adapted from Markievicz – A Most Outrageous Rebel by Lindie Naughton (Merrion Press, 2017)

No comments yet.