Spent a couple of hours as part of a panel discussion on the BBC World Service’s The Forum on Votes for Women and early parliamentarians, with Bridget Kendall asking the questions. Also speaking were Jad Adams and Dr Nikita Sud, who outlined the history of women’s suffrage in general (Jad) and in India (Nikita).

Spent a couple of hours as part of a panel discussion on the BBC World Service’s The Forum on Votes for Women and early parliamentarians, with Bridget Kendall asking the questions. Also speaking were Jad Adams and Dr Nikita Sud, who outlined the history of women’s suffrage in general (Jad) and in India (Nikita).

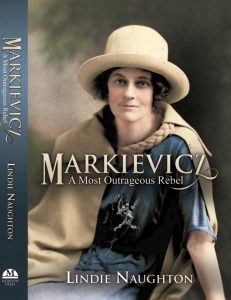

My job was to explain the significance of Constance Markievicz, the first woman elected to the House of Commons, to a world-wide audience many of them non-English speakers. They wouldn’t have a clue about Irish politics, nor would they be familiar with people like James Connolly, W.B. Yeats and Maud Gonne.

The programme goes out on the BBC World Service from Saturday 7 April to Tuesday 10 April, depending on where in the world you are located. In the UK and Ireland, the first broadcast will be on the evening of Saturday 7 April at 8pm and possibly also on Tuesday 10 April (8am). Please go tohttp://www.bbc.co.uk/worldserviceradio/help/faq for times and how to listen.

Here’s how I should have answered the questions (I think!).

So who was Markievicz and how did an Irish woman with a Polish name become the first woman elected to the British House of Commons?

Constance Markievicz, an upper-class Irish artist married to a Polish count, had joined the fight for Ireland’s independence from Britain around 1906. After becoming a member of Sinn Fein, a party dedicated to promoting Irish independence, she quickly rose up the ranks and in 1909, was the founder of a republican version of the Boy Scouts.

Because of the appalling poverty she witnessed in the city of Dublin, she was firmly on the side of the workers during the Lock-Out of 1913, when workers who joined a union were barred from their jobs on the trams, in the docks and in factories. For several months, she supervised a soup kitchen for the families of the workers so winning the respect of working men and women.

When World War 1 began in 1914, hard-line Irish republicans decided that “England’s difficulty was Ireland’s opportunity” and fixed the date of Easter 1916 for an Irish insurrection. On Easter Monday, a new Irish republic was declared promising equal rights and equal opportunities to all its citizens, men and women, rich and poor; a noble aspiration. The fighting, confined mainly to Dublin, lasted less than a week. After the surrender, its leaders, including Markievicz, were condemned to death. On grounds alone of her sex, she was spared.

Ireland at the time was part of the United Kingdom of Britain and Ireland. Like Scotland and Wales, it did not have a parliament of its own, but held 103 seats in the House of Commons. After the Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act was passed on 18 November 1918, women over 30 could stand for election as members of parliament. Although in prison at the time for her republican activities, Markievicz was asked to stand for the Sinn Fein party. She won her seat by a landslide, becoming the first ever woman elected to the House of Commons.

Like the other Sinn Fein members elected, she did not take her seat, but instead became part of the Irish government which held its first meeting in January 1919. She was also appointed Minister for Labour, so becoming only the second woman in Europe to hold a cabinet seat. This Irish government was illegal and suppressed by the British authorities, with two years of war following.

It’s worth noting that rebellious women often came from privileged backgrounds. Education and privilege had opened up the world to them, but they had found the door to that world slammed in their faces, purely on grounds of gender. In newly established social and political movements and in industries (such as aviation), which hadn’t yet decided to keep them out, they found a place.

Was Markievicz a suffragist?

Not in the strict sense of the word. She had attended suffrage meetings in her youth, but top priority for her was the establishment of a socialist Irish Republic with equal rights for men and women. Other prominent women in the republican movement argued that getting women the vote should take priority so that they could have some say in the shape the independent Ireland would take. Markievicz certainly supported the suffragist movement, and was well aware that the men fighting for Irish independence were not always interested in promoting women’s rights. Still, under the constitution for the Irish Free State, which was set up in 1922, all Irish women over the age of 21 were given the vote.

establishment of a socialist Irish Republic with equal rights for men and women. Other prominent women in the republican movement argued that getting women the vote should take priority so that they could have some say in the shape the independent Ireland would take. Markievicz certainly supported the suffragist movement, and was well aware that the men fighting for Irish independence were not always interested in promoting women’s rights. Still, under the constitution for the Irish Free State, which was set up in 1922, all Irish women over the age of 21 were given the vote.

Did Ireland have female role models in history and legend?

St Brigid, who is the female patron saint of Ireland, inspired widespread devotion and her feast day of February 1 is celebrated. There were also flamboyant women warriors like Queen Medhb and Grace O’Malley, who met Queen Elizabeth 1 in London. Markievicz named her daughter after Queen Medhb, who was buried on the top of a mountain near where she grew up in the west of Ireland. Not to be dismissed is the reverence accorded Mary, the mother of Jesus, by many Catholics and the important role nuns played in both health and education in Ireland. In literature Ireland was often referred to allegorically as “Kathleen Ni Houlihan”.

What difference did getting the vote make for Irish women?

In the second Irish government of 1921, five women, including Markievicz, were elected. That figure had dwindled to one by 1944. In the meantime, successive Irish administrations, dominated by a right-wing and repressive Catholic clergy, had clawed back the hard-earned rights won by women such as Markievicz. Women had to retire from their jobs when they married, or would not be accepted for certain jobs in the first place. They could not sit on juries. Divorce and contraception were taboo subjects. Books and films were censored. The tide only began to turn in the 1970s when women again took to the streets, not just in Ireland but all over the world. In 1979, Maire Geoghegan Quinn became the first woman to hold a cabinet position since Markievicz 60 years earlier. In 1990, Mary Robinson was appointed Ireland’s first female President and in 1997, Mary Harney became Ireland’s first deputy prime minister.

In 2016, the centenary of the Easter Rising, 35 women were elected to parliament with 25 of 40 constituencies having at least one female representative. Even if the institutions of the state remain male dominated and overwhelmingly conservative, some progress has been made.

No comments yet.